BIG BANDS, PART 2: THE TRADITION CONTINUES

In the late 1940s Lionel Hampton did not just lead a big band - he led a huge one. Consisting of five trumpets, four trombones, six saxophones, piano, guitar, bass (often two of them), drums and his own vibes, Hamp's unit rivaled only that of Stan Kenton in both size and volume.

In the late 1940s Lionel Hampton did not just lead a big band - he led a huge one. Consisting of five trumpets, four trombones, six saxophones, piano, guitar, bass (often two of them), drums and his own vibes, Hamp's unit rivaled only that of Stan Kenton in both size and volume.

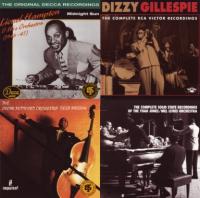

Midnight Sun (Decca GRD 625, 66:58) presents twenty recordings (including six excellent small group sides) from 1946 and 1947, an especially fresh period for Hamp. Responding to current jazz trends, he had begun stocking his ranks with young, bop-conscious players like trumpeters Jimmy Nottingham, Joe Wilder, and Kenny Dorham, trombonists Booty Wood and Britt Woodman, tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin (who was not yet eighteen years old when he joined the band), and bassist Charles Mingus. And Hampton's own playing here on "Airmail Special," for instance, demonstrates that he was an influential figure in the transition from swing to bop. But swing also is well represented in the person of Texas tenor Arnett Cobb, prominently featured on "Rockin' in Rhythm," "Airmail Special," and "Cobb's Idea."

The arrangements also reflected this modernist tinge, particularly on pianist Milt Buckner's "Goldwyn Stomp," which quotes Gillespie's "Anthropology" and alludes to Diz's "Things to Come" and "One Bass Hit," and "Hawk's Nest," with its complex harmonies and traces of bitonality. Charles Mingus' "Mingus Fingers," a three-minute concerto for his bass (played both arco and pizzicato), features atonality, dense and raucous polyphonic passages, and the effective use of woodwind colors (notably Bobby Plater's flute). Although slightly disjointed, somewhat overambitious, and marred by Hamp's intrusive and irrelevant vibes solo - he really didn't "get" Mingus (but who did, back then?) - the piece shows undeniable signs of Mingus' unique genius.

From his glassy-noted introduction to the two-part "Rockin' in Rhythm" to his lovely composition, "Midnight Sun," a ballad with an inherent double-time feel, Hamp, his vibes, and his oversized ego are never far from center stage. An irrepressible entertainer, he also is heard in this set singing, drumming, and playing the piano in his patented two-finger style. But it is as a bandleader that Hampton deserves praise, for having assembled this ensemble of exciting young players, giving them room to blow (between his inevitable solos), and swinging along with them.

* * *

There is a nasty rumor going around that bebop killed the big bands. Not true. Commercially, the swing bands fell victim to a combination of factors: inflated travel costs, changing public tastes, competition from popular singers. And artistically, big band swing, by and large, simply went stale. By the early 1940s, what was once a vibrant idiom had calcified into a predictable, easily duplicated, and, frankly, dull routine.

So it is not surprising that the handful of bands that survived the demise of the Swing Era and remained creative to the end of the decade (and beyond) were those whose leaders had the vision to incorporate at least some of bebop's innovations: Ellington, Basie, Herman, Hampton, and only a few others. (Hampton, for one, also infused his music with touches of early rhythm and blues.) And through the post-Swing Era years and decades a small number of new bands did arise and achieved artistic - if not commercial - success by melding new musical currents with a firm grounding in that swinging tradition.

From 1937 to 1944, trumpeter and bebop pioneer Dizzy Gillespie worked in the big bands of Teddy Hill, Cab Calloway, Lucky Millander, Earl Hines, Duke Ellington (subbing for about a month), and Billy Eckstine, whom he served as musical director. His roots in the idiom were deep and strong. In the spring of 1946 he decided, against all odds, to translate his brand of jazz into a big band format.

Between August 1947 and July 1949, Gillespie's band cut 28 sides for RCA Victor, all of which are reissued in the indispensable set, The Complete RCA Victor Recordings (Bluebird 66528, two CDs, 2:09:24). Also included are three 1937 tracks featuring Diz with the Teddy Hill band, his solo spot ("Hot Mallets") from a 1939 Lionel Hampton all-star date, four master takes and three alternates by Diz's 1946 combo (with Don Byas on tenor saxophone and Milt Jackson suffering, literally, from bad vibes), and a 1949 Metronome all-star session, where the personnel reads like a who's who of bebop.

Gillespie's big band was just over a year old when it hit the Victor studios in August 1947. The ensembles are tight, far better than on its often ragged Musicraft sides of 1946, playing hip, forward-looking charts by Tadd Dameron, Gil Fuller, and the band's pianist, John Lewis. Diz, bold, brash, and brimming with youthful exuberance, was the primary soloist, but up-and-coming players like baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne (on "Ow" and "Stay On It"), tenor saxophonist James Moody (typically brilliant on "Oop-Pop-A-Da"), and bassist Ray Brown (who takes center stage on a beautifully remastered "Two Bass Hit") are also featured.

In 1939, Gillespie was introduced to Afro-Cuban music by Mario Bauzá, a section mate in Cab Calloway's band and one of the unsung music makers of the last century. (Beginning in the 1940s, Bauzá, as musical director for Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra, helped found the genre known, popularly, as "Latin jazz," and more accurately as "Afro-Cuban jazz.") By December 1947, Gillespie, at Bauzá's urging, had added Cuban hand drummer Chano Pozo to the band and began incorporating these complex, exotic rhythms into its repertoire. The eight sides recorded that month reflect Pozo's dominating presence and stand as early milestones in the Afro-Cuban-jazz fusion.

Gillespie's "Algo Bueno" (a.k.a., "Woody 'n You") is one of his most harmonically ingenious and frequently played compositions in this vein. Dameron's "Cool Breeze" and "Good Bait," Fuller's "Ool-Ya-Koo," and Linton Garner's "Minor Walk" all get a polyrhythmic lift from Pozo's drum work. Even more momentous is George Russell's two-part, six-minute "Cubana Be/Cubana Bop," an advanced work that employs Afro-Cuban rhythms, modality, dense harmonies, composed polyphony, and a compelling drum-and-chant interlude by Pozo. Finally, there is the Gillespie-Fuller-Pozo masterpiece, "Manteca," one of the all-time classic jazz recordings, and among the most successful blendings ever achieved of jazz and Afro-Cuban elements.

Due to a musicians' union recording ban a full year passed before the band returned to the studio in December 1948. By then, the volatile Pozo was dead, shot in a bar fight, but Gillespie continued his explorations of Afro-Caribbean music with Gerald Wilson's "Guarachi Guaro." For the rest of his life it would remain one of his greatest passions. Wilson also contributed, to a May 1949 date, the oddly titled "Dizzier and Dizzier," a serenely pretty ballad that exhibits Gillespie's lyrical side.

Gillespie was both a consummate artist and a gifted entertainer. Alongside all the bebop, Afro-Cuban, and ballads there's also plenty of fun, in the form of engaging vocals by Diz alone ("I'm Be Boppin' Too") or with Kenny "Pancho" Hagood (for example, their lively scat chase on "Cool Breeze"). In the same vein are three delightful appearances by singer and Gillespie sidekick Joe Carroll - a wild scat chorus on "Jump Did-le Ba," scat obbligatos on "Hey Pete! Le's Eat More Meat," and a witty performance of Mary Lou Williams' bebop fairy tale, "In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee". Young balladeer Johnny Hartman croons four tunes, displaying his solid musicianship and full-bodied baritone, but his style is not yet fully formed.

Instrumentally, the band was without peer. Featured soloists during its Victor years included, at various times, trombonist J.J. Johnson, alto saxophonists John Brown and Ernie Henry, and tenor saxophonists George "Big Nick" Nicholas, Budd Johnson, and Yusef Lateef. Bassist Al McKibbon provides rock-solid support and drummer Kenny Clarke plays a vital role on the December 1947 (Chano Pozo) sessions.

Despite his prolific and groundbreaking small group work, Gillespie was, to the end, a big band partisan, so it pained him greatly when economics forced him to disband in May 1950. At various times over the next four decades he would attempt to reassemble a big band. Many were outstanding, but few, if any, could compare to the groundbreaking ensemble that cut these landmark recordings.

* * *

Bassist Oscar Pettiford was one of the architects of bebop, the most influential player on his instrument after Jimmy Blanton, and, strangely, one of the most forgotten of all the giants of jazz. In the mid 1950s, O.P. led a medium-sized big band with an unusual instrumentation (two trumpets, trombone, two French horns, four reeds, piano, bass, drums, and harp), an innovative and multi-colored working group that, unfortunately, didn't work very much.

Deep Passion (Impulse GRD 143, 1:07:50) comprises the two albums that Pettiford's band made for ABC-Paramount in 1956 and 1957, and it is wonderful to have this valuable material available again after so many years in record label oblivion. The music, arranged by saxophonists Gigi Gryce, Lucky Thompson, and Benny Golson (all of whom can be heard on this disc), swings with power when it needs to, but just as often it is delicate and impressionistic, characterized by muted pastels and soft textures.

Overall, these seventeen sides display a fresh, contemporary take on the classic big band concept, integrating strong bop-derived improvisation with inventive, state-of-the-art ensemble writing. Among the best are Gigi Gryce's "Two French Fries," a breath-taking chase for the French horns of Julius Watkins and David Amram; Benny Golson's moving elegy, "I Remember Clifford," which spotlights Art Farmer's fat-toned trumpet and Gryce's lyrical alto; and "Laura," a gorgeously scored production for harp, with flute and French horn playing key supporting roles. Pettiford's star-studded roster also included, at various times, trumpeter Kenny Dorham, trombonists Jimmy Cleveland and Al Grey, Jerome Richardson on flute and tenor, baritone saxophonist Sahib Shihab, and pianists Tommy Flanagan and Dick Katz.

And then there is the remarkable tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson. On his evocative ballad, "Deep Passion," and all the rest of his solo spots, Thompson displays his signature warm tone - derived from Don Byas, leavened with a touch of Lester Young - and harmonic breadth. The stunning work of his prime heightens the tragedy of Thompson's later years, when he lived as a shadowy figure on the fringes of society, often homeless and lost to the jazz world. This was one special artist, and his inexplicable decline and inactivity left a huge void in the music.

Along with his rock-solid bass, Pettiford also is heard throughout on cello, which he played pizzicato. At times, both bass and cello are clearly audible, and no credit is given for an additional bassist (except on one track, where Whitey Mitchell plays), suggesting that O.P. must have engaged in some unacknowledged overdubbing. On "Perdido" and Randy Weston's jazz waltz, "Little Niles," two of his best cello features, the sound he gets from the instrument is remarkably like Wes Montgomery's thumb-picked guitar tone. Pettiford also reveals overlooked talents as a composer with such well crafted - and superbly titled - tunes as "The Pendulum at Falcon's Lair" and "The Gentle Art of Love," among others.

It is a shame that this gifted and visionary artist, who died in 1960 at the age of thirty-eight, is seldom recognized alongside Bird and Diz and Bud and Max as one of the true founders of modern jazz. O.P. was their colleague and, in every way, their equal.

* * *

In December 1965 Thad Jones, a former Count Basie trumpeter-arranger, and drummer Mel Lewis, another big band and studio veteran, formed a rehearsal band primarily to play Jones' rich, sophisticated charts. Consisting of the cream of New York's TV and recording studio players, the band held its weekly sessions at midnight, the only time that these musicians' busy schedules would allow them to meet. Then, on Monday night, February 7, 1966, jazz history was made. The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra played its first gig at the Village Vanguard. It would remain a weekly fixture there, in one form or another, for the next four-and-half decades.

The Complete Solid State Recordings of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra (Mosaic MD5 151, five CDs, 4:25:48) comprises the band's first five albums (recorded between 1966 and 1970), along with previously unreleased tracks and alternate takes, remastered without any of the phony-sounding reverb that plagued so many late 1960s releases. The lively and informative notes were prepared by composer-arranger-multi-reed player (and Jones/Lewis alumnus) Bill Kirchner.

The set opens with material from the band's landmark debut recording, Presenting Thad Jones, Mel Lewis & the Jazz Orchestra, which stands alongside Basie's Chairman of the Board and Ellington's ... And His Mother Called Him Bill as one of the finest presentations of big band jazz in the LP era. Jones' charts are brimming with surprises and delights, like his modal swinger, "Once Around," with its deceptively simple, symmetric theme, driving ensembles, and dynamic contrasts. Tunes like the bossa nova "Don't Ever Leave Me" and the straight-ahead "Mean What You Say" display Jones' gift for creating pretty, singable melodies. If this had not been the rock-bound '60s, he might have had a parallel career as a successful songwriter. Clearly Alec Wilder recognized this when he chose to fit lyrics to Jones' poignant 3/4 ballad, "A Child Is Born." (The original instrumental version, from 1970, can be heard in this collection.)

But the masterpiece of these initial sessions is Jones' "Three and One," a sort of concerto grosso - a favorite compositional device of his - that sets a trio of his flugelhorn, Pepper Adams' baritone saxophone, and Richard Davis' bass against the larger ensemble. The second chorus moves into an astoundingly intricate saxophone soli, kept ever on course by master lead alto Jerome Richardson. When it comes to exceptional saxophone section work, five musicians playing as one, there are three milestones: Ellington's "Cotton Tail" (1940), Neal Hefti's "Cute" (for the 1957 Basie band), and Thad Jones' "Three and One."

Two sessions, from April 1967 and October 1968, capture the band in its natural habitat, the Village Vanguard. On live performances such as these, Jones not only conducted the band, he would alter his complex arrangements on the fly, cuing sections in and out behind soloists, manipulating dynamics, even changing tempos. "Thad was the organist," Jerome Richardson liked to say, "and we were the stops."

And now a couple of words about the personnel: simply terrific. Heard over the course of these forty-two tracks are trumpeters Snooky Young, Bill Berry, Jimmy Nottingham, Marvin Stamm, Richard Williams, and Danny Moore; trombonists Bob Brookmeyer, Garnett Brown, Jimmy Knepper, and Benny Powell; reed players Jerome Richardson, Jerry Dodgion, Joe Farrell, Eddie Daniels, Pepper Adams, Seldon Powell, and Billy Harper; pianists Hank Jones and Roland Hanna; and Richard Davis, whose bass not only walks, it hops, skips, and jumps.

Valve trombonist Bob Brookmeyer penned five charts in this collection, notably two from the band's first album. "ABC Blues" blends distinctive compositional elements - pointillism, dissonance, powerhouse ensembles, improvised counterpoint - with a string of distinguished solos, including a very cool one by alto saxophonist Jerry Dodgion and a surprisingly gut-bucket one by Brookmeyer. Ann Ronnell's standard, "Willow Weep for Me," becomes, in Brookmeyer's hands, an impressionist tone poem. Jones' flugelhorn solo is introspective and deliberate, gently cradling every note the way a tree branch caresses a dew drop.

"Central Park North," the title track of the band's fourth album, is one of Jones' most complex compositions. This nine-minute excursion winds through a gospel-rock-boogaloo opening section that somehow does not sound dated, a ballad interlude for Jones' flugelhorn, and a couple of funky blues solos by plunger-muted trumpet (Nottingham) and soprano saxophone (Richardson), before it returns home. "Big Dipper" illustrates the kind music that the Basie band of the late 1960s might have played had the Count's tastes been a bit less conservative. In fact, Basie had commissioned this and several other charts (among them, "The Little Pixie," "A-That's Freedom," and "The Second Race") for a planned album of Jones originals, but rejected them all because they were either too complicated or too difficult or simply not his style. And "The Groove Merchant," a catchy shuffle written by Richardson and arranged by Jones, is highlighted by another superbly executed saxophone soli, this time employing Richardson's soprano lead, one of the band's sonic trademarks.

The final album contained in this set, Consummation, offers more memorable Jones' writing. On both the title track and the multi-sectioned "Dedication," he augments the ensemble with four French horns plus tuba, exploiting these added colors to maximum advantage. The animated "Tiptoe" is distinguished by Snooky Young's tasty, cup-muted trumpet solo that wastes not a single note, some easy-going alto from Jerry Dodgion, and a tricky unison chorus for trombones and bass. Trombonist Benny Powell leads off the solo parade on the intricate, angular "Fingers" with a fleet, four-chorus tour de force that might just be his finest recorded improvisation. Also noteworthy are Jones' lilting bossa nova, "It Only Happens Every Time," and his best known piece, "A Child Is Born."

The Jones/Lewis Orchestra continued performing and recording until January 1979, when the co-leaders parted ways and Jones emigrated to Copenhagen to take over the Danish Radio Orchestra. ("Thad went to Europe," Jerry Dodgion has quipped, "and Mel got custody of the kids.") Jones fronted the Count Basie Orchestra briefly in 1985 and then returned to Denmark, where he died the following year. Lewis continued to lead the band on its weekly gigs at the Village Vanguard until his death in 1990. Since then, it has taken a new name, "the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra," and there are only a few holdovers remaining from the Thad Jones era. Still, it is gratifying that, these many decades after its inception, the tradition continues and that, as this essential collection demonstrates, the music of Thad Jones is as exciting and stimulating as ever.

Click Here to read Part One of this article: Big Bands: The Birth of Swing

© Bob Bernotas 1994; revised 2011. All rights reserved. This article may not be reprinted without the author's permission.